Works / Munkák 1976–1980. Galeria Neon, Budapest, 2017. Solo exhibition.

Works / Munkák 1976 –1980. Galeria Neon, Budapest. 2017. Solo Exhibition.

Article in Balkon Art Magazine ︎︎︎

Article in Balkon Art Magazine ︎︎︎

EVALUATION

Where do we come from, who were we, where did we go?

On works by Gábor Palotai made between 1976 and 1980.

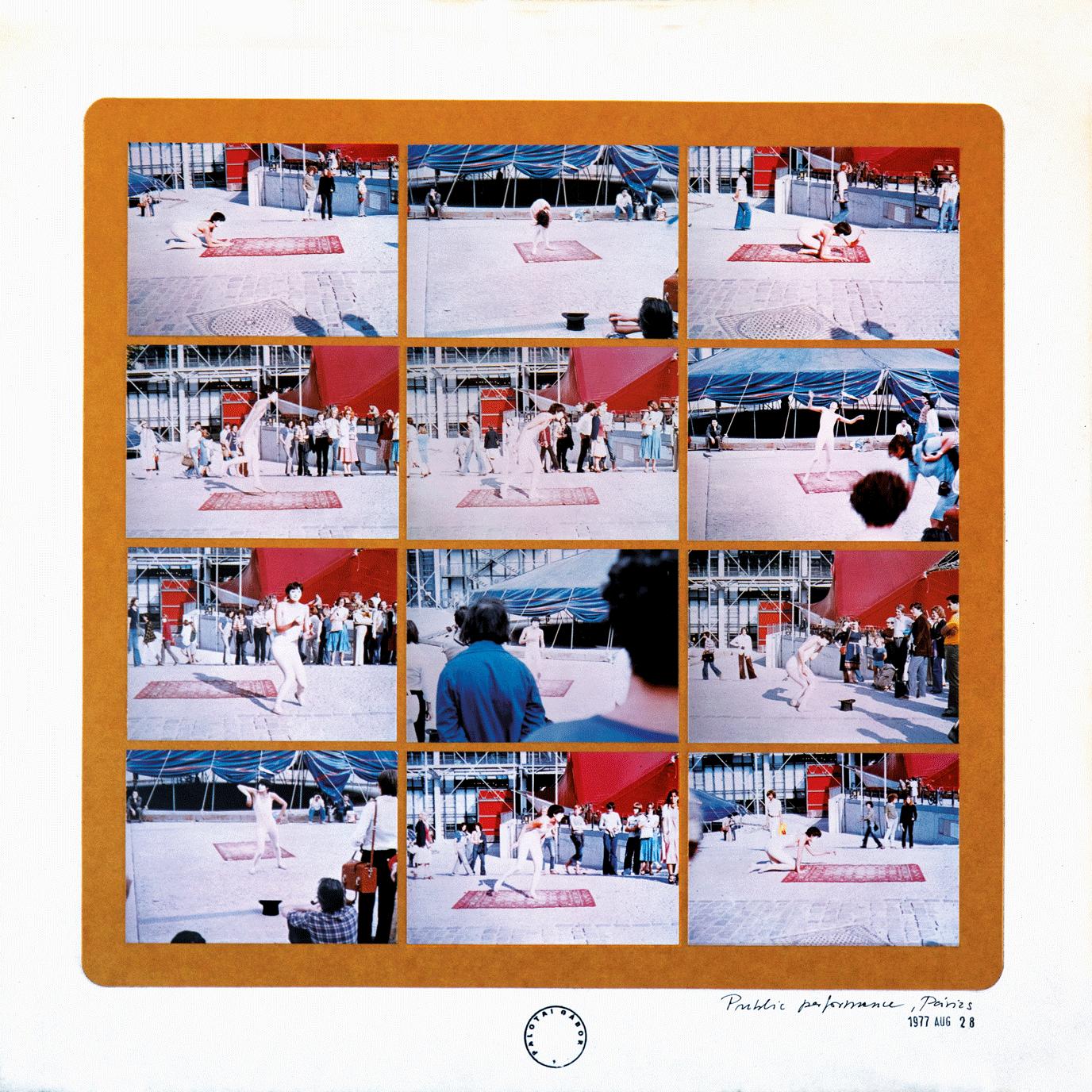

The works of art, some of which are reproduced in this book and some of which are included in the related exhibition, have not been on public display for a good forty years, and even when they were, at the time of their completion, only a limited audience had an opportunity to see them, and only for a short period of time. Their creator was a student at the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts, and the works were composed almost exclusively during this period and were, in their time, put on display as part of an end-of-the-year ritual termed evaluation and the public exhibition that was connected with it. Displays of Gábor Palotai’s works were memorable for a number of us. I was one of several people who took the trip to the school now called MOME[1] on Zugligeti Road just to see his exhibitions. Why was this? Presumably part of the explanation — and indeed this was obvious even back then — lies in the fact that these works, created alongside school exercises (often as critiques of or alternatives to compositions made as a part of formal studies), came into being as a result of the liberating, refreshingly inspirational effect of Conceptual Art, which globally transformed the last period of 20th-century art[2]. We will return to this later.

The selection of the works for the book deserves particular attention, since in the book we find a segment or synopsis of a (life)period. According to Euclid’s second postulate, any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line, and indeed if this were not true this writing could not have come about. Yet nonetheless, we will only concentrate on this segment. First, let’s consider its starting and ending points, which conceal quotes. Images no. 2 and 3, a Polaroid series entitled Portrait of the artist as a young man I.-II., 1978, refer to James Joyce. “Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes” is the motto of Joyce’s novel Portrait of a Young Man, which in the English translation of Ovid reads[3]: “Then to new arts his cunning thought applies”. In a good case scenario, this notion is essential for a beginner artist-student. In addition to the Polaroids, Gábor Palotai’s youthful portrait appears on the cover of the volume as well, in a selfportrait the title of which is a borrowing from Attila József (I might suddenly disappear, photo exercise, 1977). Palotai is seen holding a cable release in his hand, and the black-and-white pictures made from the same negative become increasingly faded towards the lower right-hand corner, thereby transforming the poet’s trope into a concrete image. The works of art in the age of mechanical reproduction simultaneously reflect on major art historical genres and the medium in use. Maintaining the encompassing theme of a self-portrait, the mirror is replaced here by the reflex camera and the brush by the cable release. The title suggests a melancholic motif, but the technique withdraws it.

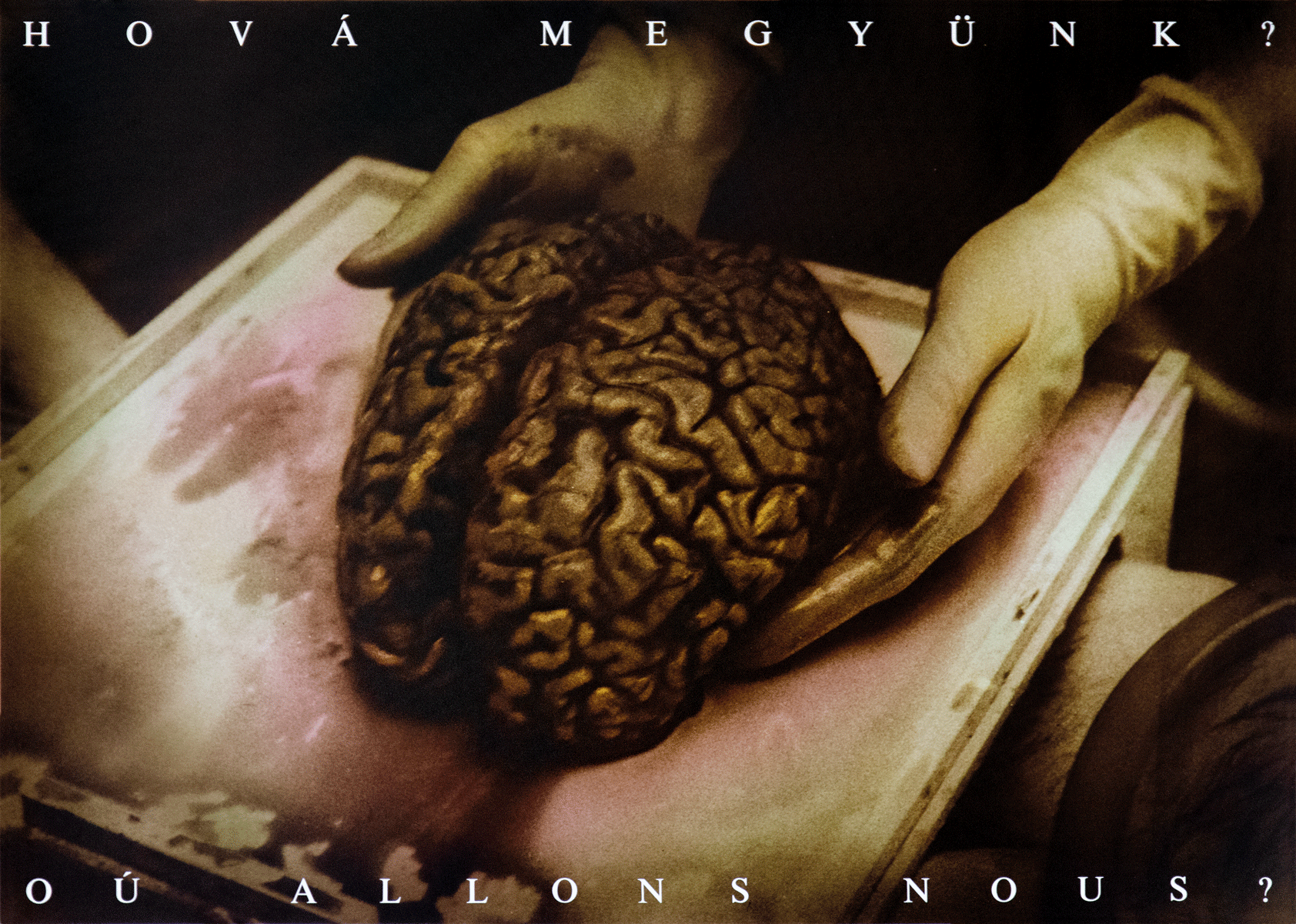

The volume’s last images — as if providing a framed structure — can be perceived as unique inverses of the first images, but also as a polysemantic conclusion: No chance. The “Pas de Chance” series, which consists of embrowned photographs coloured with an airbrush (Palotai originally handed it in as a poster and these photographs also appeared in his diploma work), was augmented with the inscription “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going” in Letraset letters. A footnote is needed here. (There was no Photoshop back then.) This is a unique secession from the conceptual which, however, retains the basic theme: compared with traditional conceptual approaches, the unusually altered photographs shift towards narrative. The inscription is a reference to Paul Gauguin’s 1897 painting,[4] but in the backgrounds we can also discover, among other things, a recurring motif from Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet) from 1957. We became acquainted with Bergman’s film and its famed chess party scene in one of the film events of the Faculty of Humanities of Eötvös Loránd University, which was an essential location for our weekly 4-5-hour film consumption habit.

Where do we come from?

The use of the plural form in this text is justified because I had an opportunity to follow, intensely and at a fairly close distance, the process by which these works were created, and I also survived the end of the 1970s parallel with the artist. This period could be described today as a steadily hopeless and dreary phase of the Kádár era in Hungary, in other words an unfriendly period of the version of “existing socialism” that was temporarily stationed in the Carpathian Basin, a period just before its fall, though by no means a period of flowering.

“I wish there were documents of this period, of this current period as well in my works. A photograph is replenished in the course of time, with time. It preserves the air from the situation which I photographed. A drawing doesn’t change.” – said Gábor Palotai during a conversation between the two of us recorded on 9 December 1980. Indeed, this period appears not only in the photographs, but also in the altered postcard collages, plans and studies (Plan for an oil painting (Sleeping), 1978), in which it bears unexpected connotations and enriches the original expectations with inspiring surprises for today.

A characteristic feature of the period, the “situation” was, for example, the obligatory model drawing during the college years, a frequent concomitant of academic studies, which was particularly frustrating in the context of technical mediums newly put into practice. The numerous model studies in the book were created parallel to this educational expectation. They were made with photographs and not graphic tools. The true source and basis for this decision was the agglomeration of information which spread through alternative channels and which informed us of the international functional change in current, contemporary art.

The inspiring present accessible in samizdat publications fell outside of the permitted cultural sphere, and because it was invisible in everyday life, it had to be created as a parallel culture, alongside the imparted tasks, because of course the obligatory duties also proliferated. I was present when the author burned several dozen drawings in the garden of his weekend house in Leányfalu: a series of photographs showing this is reproduced in this book. In memoriam, 1979. One of the “in the traditional sense” graphic design works reproduced in this book was the cover for his mother, the textile designer Éva Németh’s[5] catalogue. Another is a book: Captain Nemo, book design I-II., 1977, IBM magnet card, Letraset, 50x50 cm. In the latter there is a magnet card in a case. Its pair shows an image of the technical device with a description. “The IBM card holds an entire novel and can be played at home” (…) “Works of world literature are recorded and stored on IBM cards.”[6]

Who were we?

Around 1977, video was the novelty. A separate section was devoted to it at Documenta in Kassel. Alongside the super 8 film, independent filmmakers slowly began to familiarize themselves with electronics. The instantaneousness of the image was initiated by the Polaroid and the video, although it was not yet obvious how quickly we would then pass over the period of instant imagery. “Everything is still ensuing, but we are waiting” wrote Tibor Hajas in 1977 in the first publication in Hungary that focused solely on video art (The beauty of cathode rays, stencilled inset.)

Several of the pictures in the volume show works having to do with television or video. Everyday-symbol /1’51’’/, 1978. The everyday symbol has become esoteric in our time. The monoscope, the TV clock, not to mention the cathode ray tube screen have all disappeared. They require explanations. In an era of continuous information flow we should point out that in 1975 in Hungary the weekly average television broadcast was 67 hours, and there were no broadcasts on Mondays until 1989. In 1975, nearly two and a half million households had television sets, the majority of which were black and white.[7] Video art – 1 program, which was made in 1978 and consists of 9 colour Polaroid pictures, successfully unites the conceptual technique already developed with nude studies (making the model move and creating a serial quality by placing photographs made from different viewpoints side by side) and the potentiality of assigning a turned-off television object, representing technical media, to which, as foreign elements, the black and white covers bring a sculptural connotation. The idea is confirmed by the title (Video art – 1 program), through which the work is in a relationship with making video similar to the relationship between the window and shutter variations of My Daily Exposures of 1978 and photography.

In the exhibition catalogue Concept – Conception[8] Dóra Mauer writes “Conceptual Art (...) was a true global paradigm shift and we have been thinking differently about art since. Conceptual Art liberated creative reflection applicable to any phenomenon in the world. The better examples of contemporary Hungarian art (at least in my opinion) could be called postconceptual.” Later, in an interview conducted with Maurer, she added: “…post-conceptual (…) this way of thinking, through which people went, meaning that their brains turned over a bit – this is inherent in all of the subsequent art, whether they are painting, sculpting or making films (…) It was inspiring. One felt liberated….”[9] Gábor Palotai’s possibly last work in Hungary was his participation in Dóra Maurer’s television work on photography in the series “Műhelytitkok” (Secrets of the Studio) for which he took photographs of Miklós Erdély’s action Photogram with Ladder.

Where did we go?

Undoubtedly, Gábor Palotai was always preparing to be an artist. Even before he had begun his studies at the Academy of Applied Arts, his graphic works appeared in the cultural weekly publication Élet és Irodalom (Life and Literature). It would be interesting to compare motifs of the graphic works published between the first and sixteenth pages of the 7 August 1976 issue of Élet és Irodalom with the formal elements of the much later Unreadable Messages,[10] which received the Red Dot Design Award, but this will have to wait.

For the observant reader, it is in all certainty obvious that a cultural-historical-art marketable appropriation of the works made between 1976 and 1980 and published in this book — in other words, a scholarly and public acknowledgement of their merits — can only begin now. After receiving his diploma, Gábor Palotai left for Stockholm, and he only returned to Hungary once his Swedish passport enabled him to do so safely. It is another characteristic of this period that his departure, in other words, his moving from one European city to another European city, was not a simple act, but a prohibited and often punishable crime under the Kádár regime. It is not insignificant that his thesis, written in dialogue format and connected with his diploma work, begins with a Xerox copy and alludes to Franz Kafka’s short story The Departure. “So you know your goal?” he asked. “Yes…Out of here, that is my goal.”

We could ponder the magical-fetishist form of historical consciousness, which, like the Holy Crown in 1978, has unexpectedly returned to Hungary. Floor upbuilding. But art as an alternative to freedom apparently stands the test of time, and that is always heartening.

Budapest, 4 June, 2017.

Miklós Peternák

[1] In 2015 Gábor Palotai was elected as honorary professor of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME).

[2] Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s. New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999. Hans D. Christ, Iris Dressler (ed.): Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression: 60s–80s / South America / Europe. Ostfildern: Hantje Cantz Verlag, 2010.

[3] Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. (The Story of Daedalus and Icarus, Book VIII, line 188). Translated by Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden, et al. http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.8.eighth.html

[4] Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? 1897–98. Oil on canvas, 139.1 x 374.6 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Cat. Wildenstein 561. http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/where-do-we-come-from-what-are-we-where-are-we-going-32558

[5] http://nemetheva.com

[6] Historical reference: In Hungary the KSH (Central Statistical Bureau) began to use IBM 370/155 computers for data processing in 1974. https://www.ksh.hu/mult_torteneti_kronologia

[7] Purchase data in 1975 were the following: of the nearly 250 thousand television sets sold, barely more than three thousand were colour TVs. In: Magyarország a XX. században. (Hungary in the 20th Century) Szekszárd: Babits Kiadó, 1996-2000. vol. III. A Magyar Televízió története. (The History of the Hungarian Television) Miklós Kaposy (pp. 459–498) http://mek.oszk.hu/02100/02185/html/516.html#519

[8] Koncept koncepció, szemelvények / Concept Conception, Extracts. Katalógus elõszó / Introduction: idézetek /quotations. Budapest: OSAS, 2008.

[9] Interview with Dóra Maurer (2014) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmgYlxglvKg

[10] https://red-dot-21.com/p/design-products/books/typography/unreadable-messages/

Where do we come from, who were we, where did we go?

On works by Gábor Palotai made between 1976 and 1980.

The works of art, some of which are reproduced in this book and some of which are included in the related exhibition, have not been on public display for a good forty years, and even when they were, at the time of their completion, only a limited audience had an opportunity to see them, and only for a short period of time. Their creator was a student at the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts, and the works were composed almost exclusively during this period and were, in their time, put on display as part of an end-of-the-year ritual termed evaluation and the public exhibition that was connected with it. Displays of Gábor Palotai’s works were memorable for a number of us. I was one of several people who took the trip to the school now called MOME[1] on Zugligeti Road just to see his exhibitions. Why was this? Presumably part of the explanation — and indeed this was obvious even back then — lies in the fact that these works, created alongside school exercises (often as critiques of or alternatives to compositions made as a part of formal studies), came into being as a result of the liberating, refreshingly inspirational effect of Conceptual Art, which globally transformed the last period of 20th-century art[2]. We will return to this later.

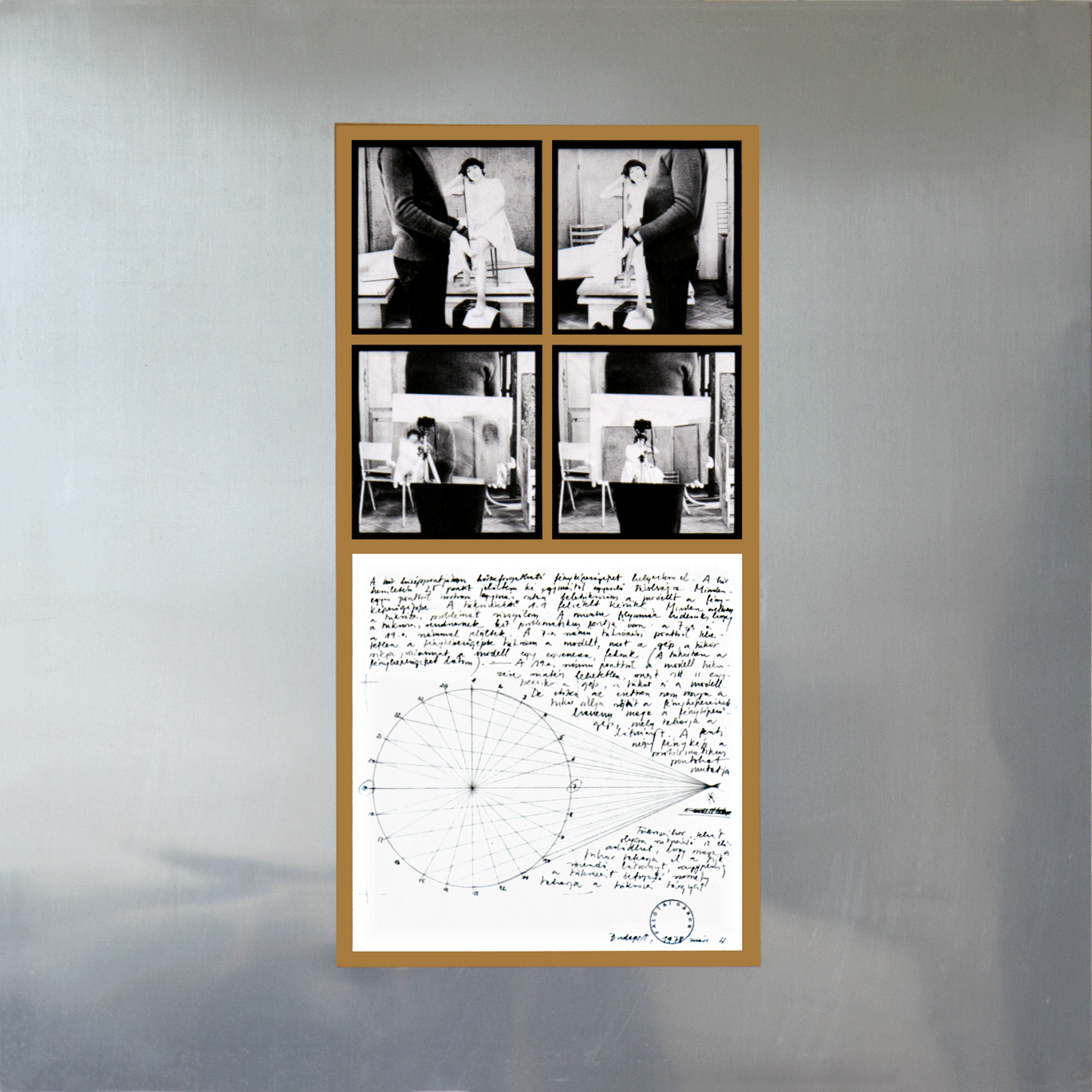

The selection of the works for the book deserves particular attention, since in the book we find a segment or synopsis of a (life)period. According to Euclid’s second postulate, any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line, and indeed if this were not true this writing could not have come about. Yet nonetheless, we will only concentrate on this segment. First, let’s consider its starting and ending points, which conceal quotes. Images no. 2 and 3, a Polaroid series entitled Portrait of the artist as a young man I.-II., 1978, refer to James Joyce. “Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes” is the motto of Joyce’s novel Portrait of a Young Man, which in the English translation of Ovid reads[3]: “Then to new arts his cunning thought applies”. In a good case scenario, this notion is essential for a beginner artist-student. In addition to the Polaroids, Gábor Palotai’s youthful portrait appears on the cover of the volume as well, in a selfportrait the title of which is a borrowing from Attila József (I might suddenly disappear, photo exercise, 1977). Palotai is seen holding a cable release in his hand, and the black-and-white pictures made from the same negative become increasingly faded towards the lower right-hand corner, thereby transforming the poet’s trope into a concrete image. The works of art in the age of mechanical reproduction simultaneously reflect on major art historical genres and the medium in use. Maintaining the encompassing theme of a self-portrait, the mirror is replaced here by the reflex camera and the brush by the cable release. The title suggests a melancholic motif, but the technique withdraws it.

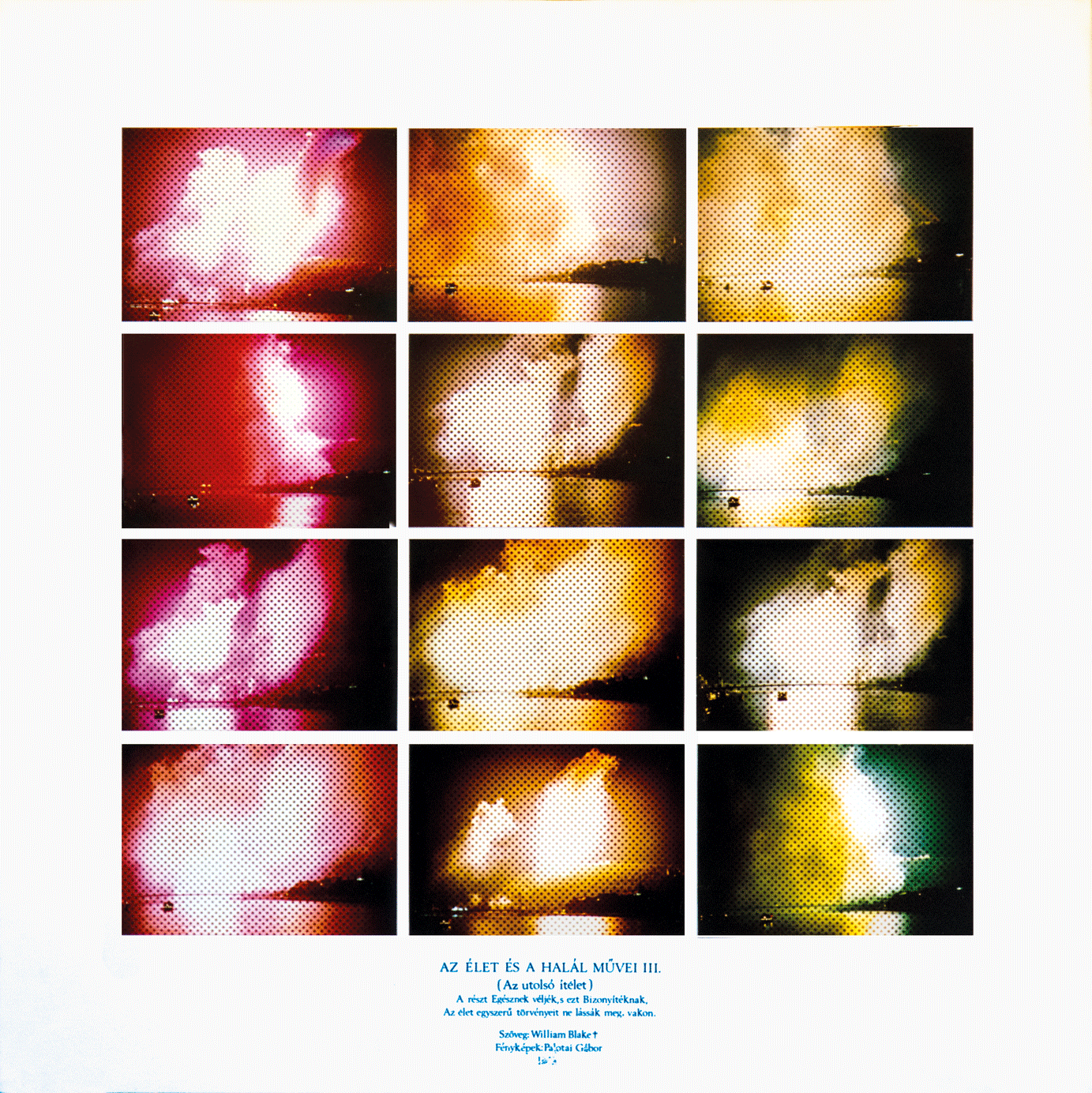

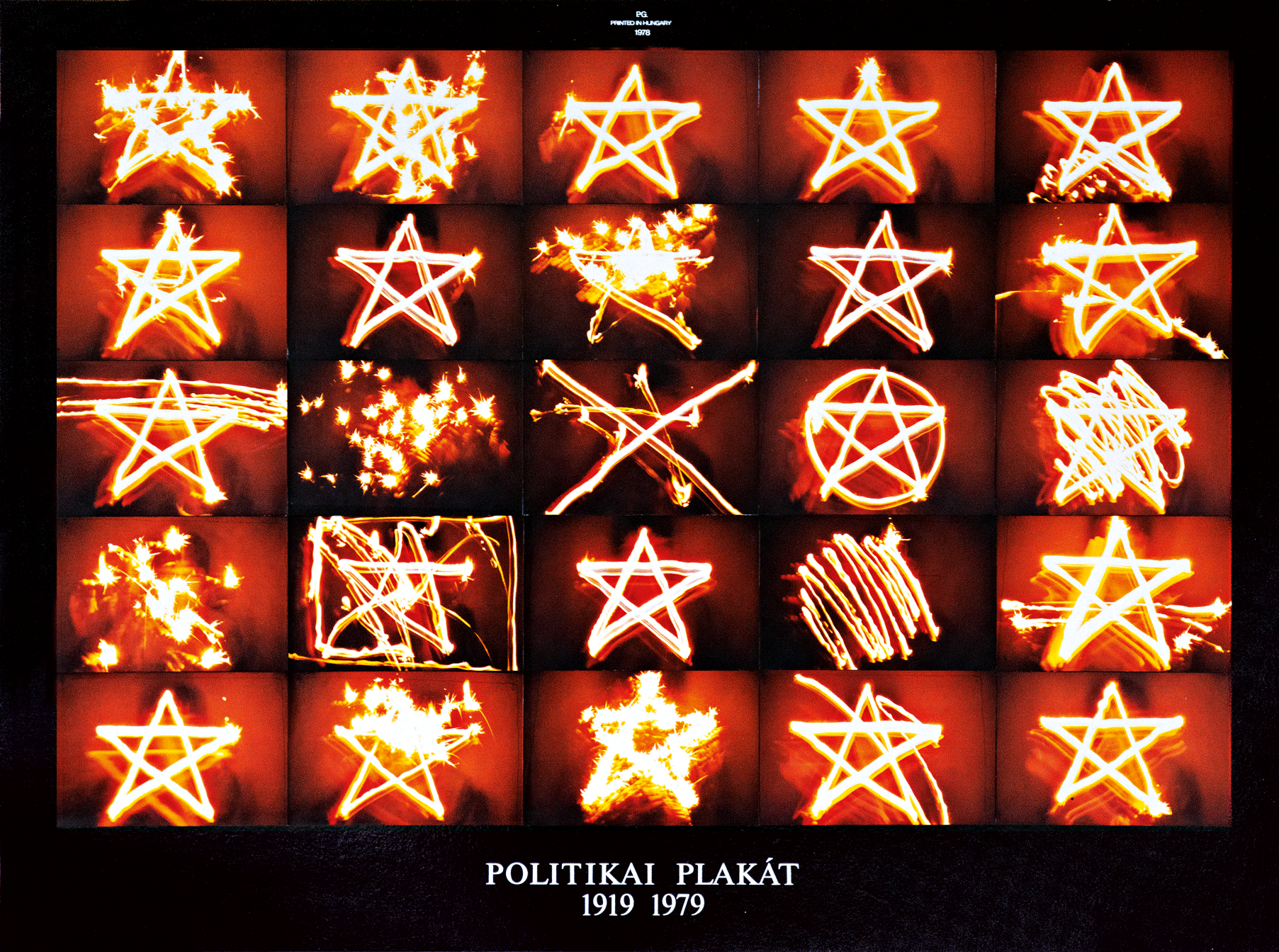

The volume’s last images — as if providing a framed structure — can be perceived as unique inverses of the first images, but also as a polysemantic conclusion: No chance. The “Pas de Chance” series, which consists of embrowned photographs coloured with an airbrush (Palotai originally handed it in as a poster and these photographs also appeared in his diploma work), was augmented with the inscription “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going” in Letraset letters. A footnote is needed here. (There was no Photoshop back then.) This is a unique secession from the conceptual which, however, retains the basic theme: compared with traditional conceptual approaches, the unusually altered photographs shift towards narrative. The inscription is a reference to Paul Gauguin’s 1897 painting,[4] but in the backgrounds we can also discover, among other things, a recurring motif from Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet) from 1957. We became acquainted with Bergman’s film and its famed chess party scene in one of the film events of the Faculty of Humanities of Eötvös Loránd University, which was an essential location for our weekly 4-5-hour film consumption habit.

Where do we come from?

The use of the plural form in this text is justified because I had an opportunity to follow, intensely and at a fairly close distance, the process by which these works were created, and I also survived the end of the 1970s parallel with the artist. This period could be described today as a steadily hopeless and dreary phase of the Kádár era in Hungary, in other words an unfriendly period of the version of “existing socialism” that was temporarily stationed in the Carpathian Basin, a period just before its fall, though by no means a period of flowering.

“I wish there were documents of this period, of this current period as well in my works. A photograph is replenished in the course of time, with time. It preserves the air from the situation which I photographed. A drawing doesn’t change.” – said Gábor Palotai during a conversation between the two of us recorded on 9 December 1980. Indeed, this period appears not only in the photographs, but also in the altered postcard collages, plans and studies (Plan for an oil painting (Sleeping), 1978), in which it bears unexpected connotations and enriches the original expectations with inspiring surprises for today.

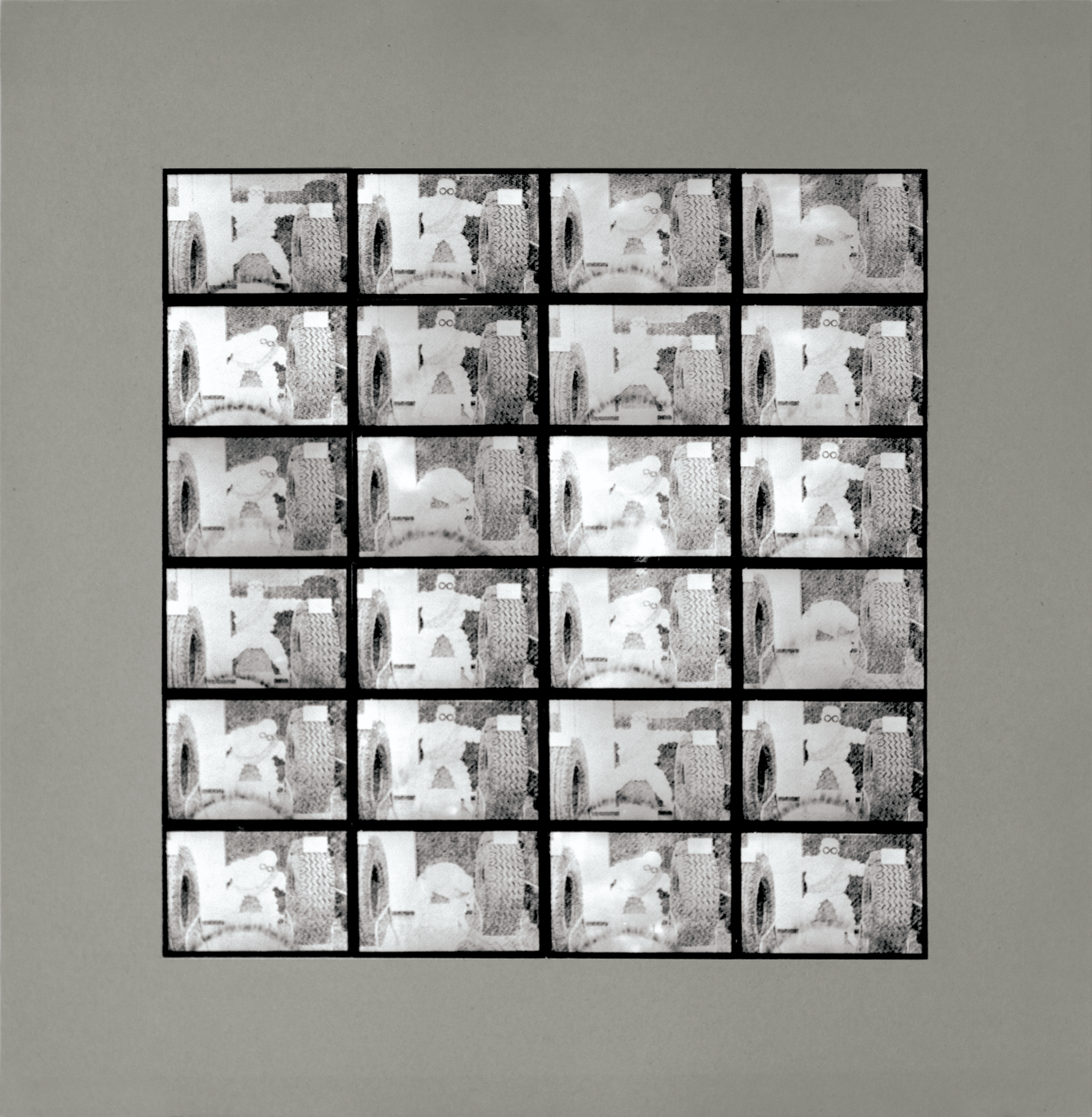

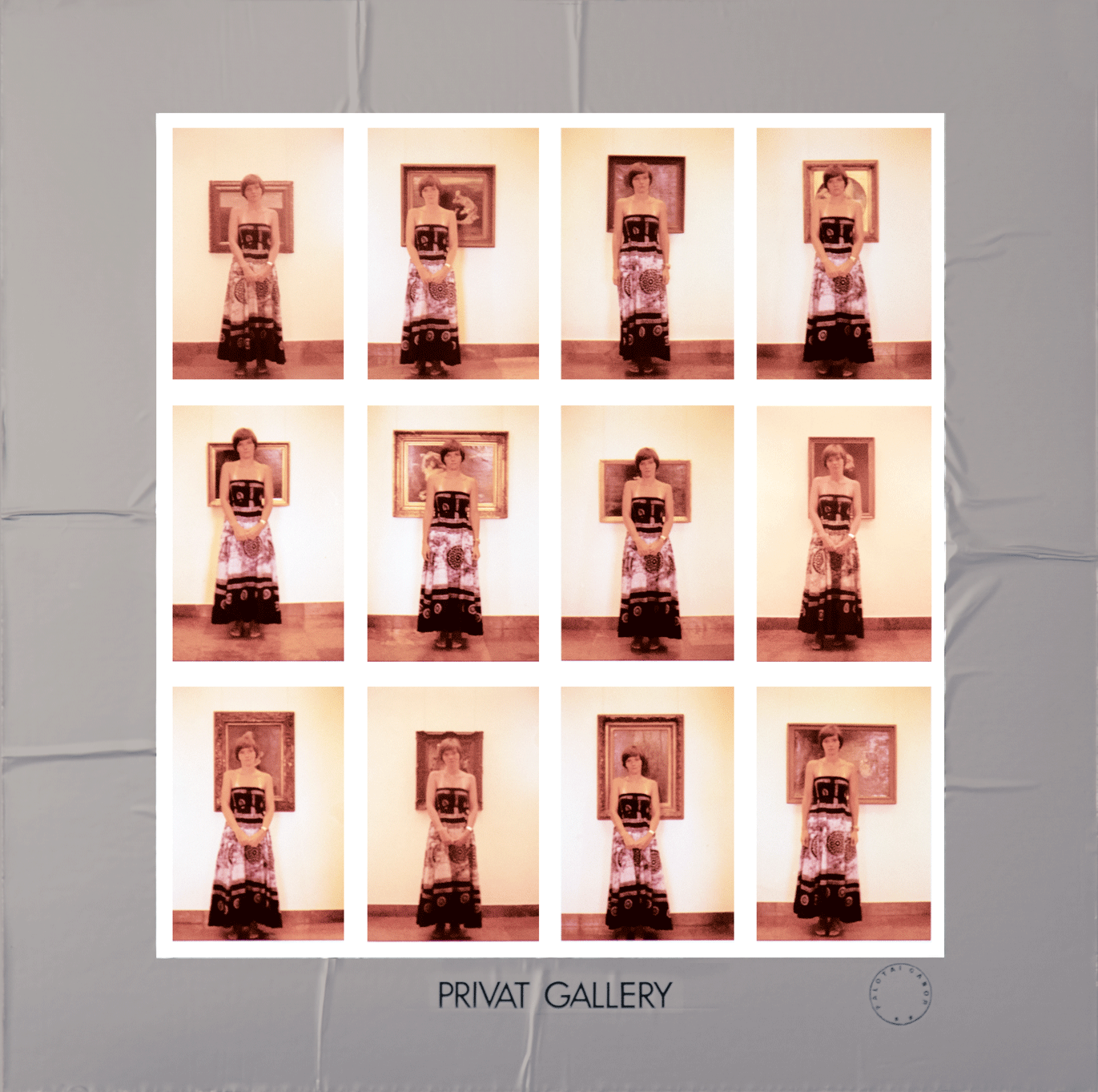

A characteristic feature of the period, the “situation” was, for example, the obligatory model drawing during the college years, a frequent concomitant of academic studies, which was particularly frustrating in the context of technical mediums newly put into practice. The numerous model studies in the book were created parallel to this educational expectation. They were made with photographs and not graphic tools. The true source and basis for this decision was the agglomeration of information which spread through alternative channels and which informed us of the international functional change in current, contemporary art.

The inspiring present accessible in samizdat publications fell outside of the permitted cultural sphere, and because it was invisible in everyday life, it had to be created as a parallel culture, alongside the imparted tasks, because of course the obligatory duties also proliferated. I was present when the author burned several dozen drawings in the garden of his weekend house in Leányfalu: a series of photographs showing this is reproduced in this book. In memoriam, 1979. One of the “in the traditional sense” graphic design works reproduced in this book was the cover for his mother, the textile designer Éva Németh’s[5] catalogue. Another is a book: Captain Nemo, book design I-II., 1977, IBM magnet card, Letraset, 50x50 cm. In the latter there is a magnet card in a case. Its pair shows an image of the technical device with a description. “The IBM card holds an entire novel and can be played at home” (…) “Works of world literature are recorded and stored on IBM cards.”[6]

Who were we?

Around 1977, video was the novelty. A separate section was devoted to it at Documenta in Kassel. Alongside the super 8 film, independent filmmakers slowly began to familiarize themselves with electronics. The instantaneousness of the image was initiated by the Polaroid and the video, although it was not yet obvious how quickly we would then pass over the period of instant imagery. “Everything is still ensuing, but we are waiting” wrote Tibor Hajas in 1977 in the first publication in Hungary that focused solely on video art (The beauty of cathode rays, stencilled inset.)

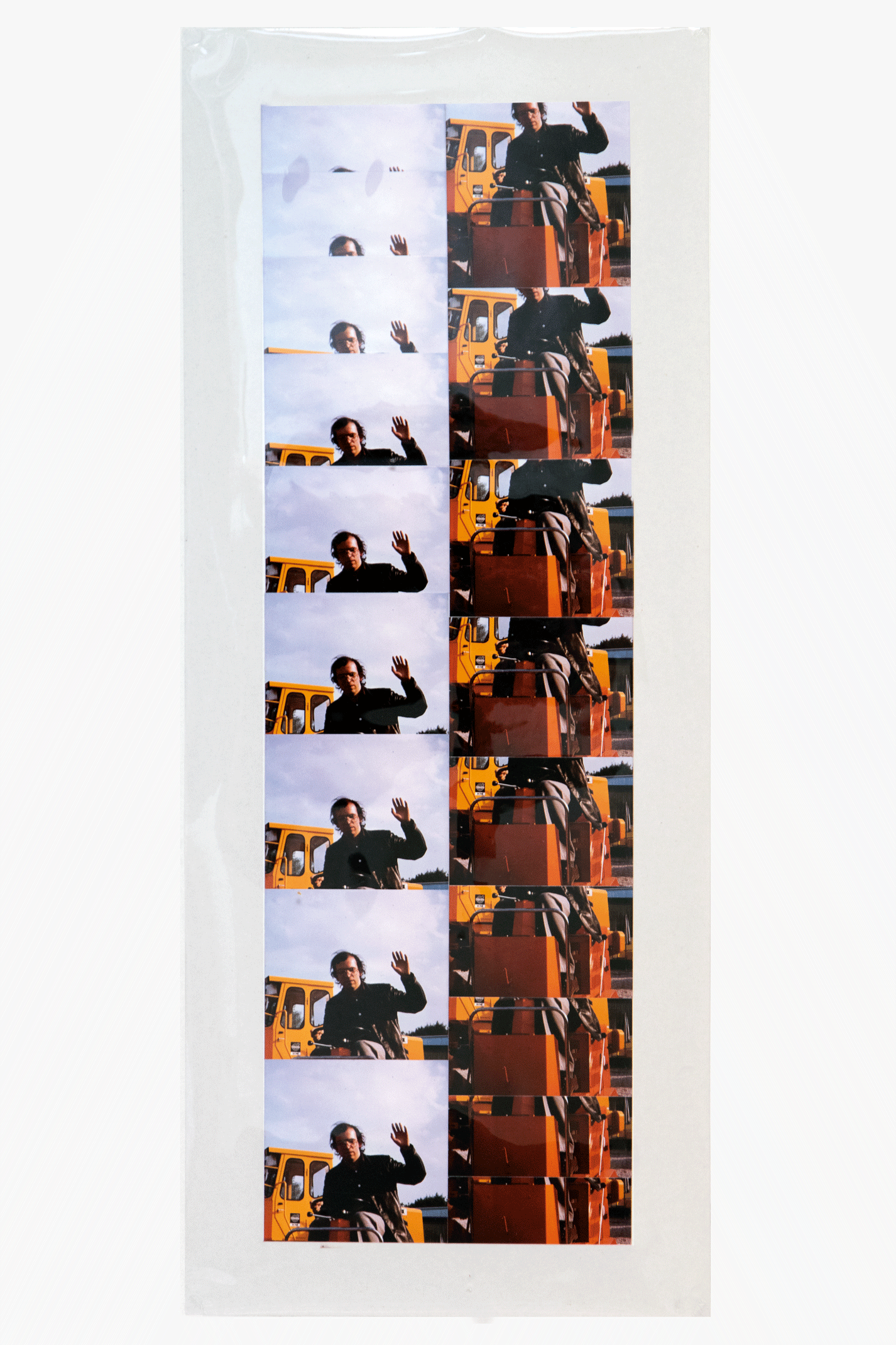

Several of the pictures in the volume show works having to do with television or video. Everyday-symbol /1’51’’/, 1978. The everyday symbol has become esoteric in our time. The monoscope, the TV clock, not to mention the cathode ray tube screen have all disappeared. They require explanations. In an era of continuous information flow we should point out that in 1975 in Hungary the weekly average television broadcast was 67 hours, and there were no broadcasts on Mondays until 1989. In 1975, nearly two and a half million households had television sets, the majority of which were black and white.[7] Video art – 1 program, which was made in 1978 and consists of 9 colour Polaroid pictures, successfully unites the conceptual technique already developed with nude studies (making the model move and creating a serial quality by placing photographs made from different viewpoints side by side) and the potentiality of assigning a turned-off television object, representing technical media, to which, as foreign elements, the black and white covers bring a sculptural connotation. The idea is confirmed by the title (Video art – 1 program), through which the work is in a relationship with making video similar to the relationship between the window and shutter variations of My Daily Exposures of 1978 and photography.

In the exhibition catalogue Concept – Conception[8] Dóra Mauer writes “Conceptual Art (...) was a true global paradigm shift and we have been thinking differently about art since. Conceptual Art liberated creative reflection applicable to any phenomenon in the world. The better examples of contemporary Hungarian art (at least in my opinion) could be called postconceptual.” Later, in an interview conducted with Maurer, she added: “…post-conceptual (…) this way of thinking, through which people went, meaning that their brains turned over a bit – this is inherent in all of the subsequent art, whether they are painting, sculpting or making films (…) It was inspiring. One felt liberated….”[9] Gábor Palotai’s possibly last work in Hungary was his participation in Dóra Maurer’s television work on photography in the series “Műhelytitkok” (Secrets of the Studio) for which he took photographs of Miklós Erdély’s action Photogram with Ladder.

Where did we go?

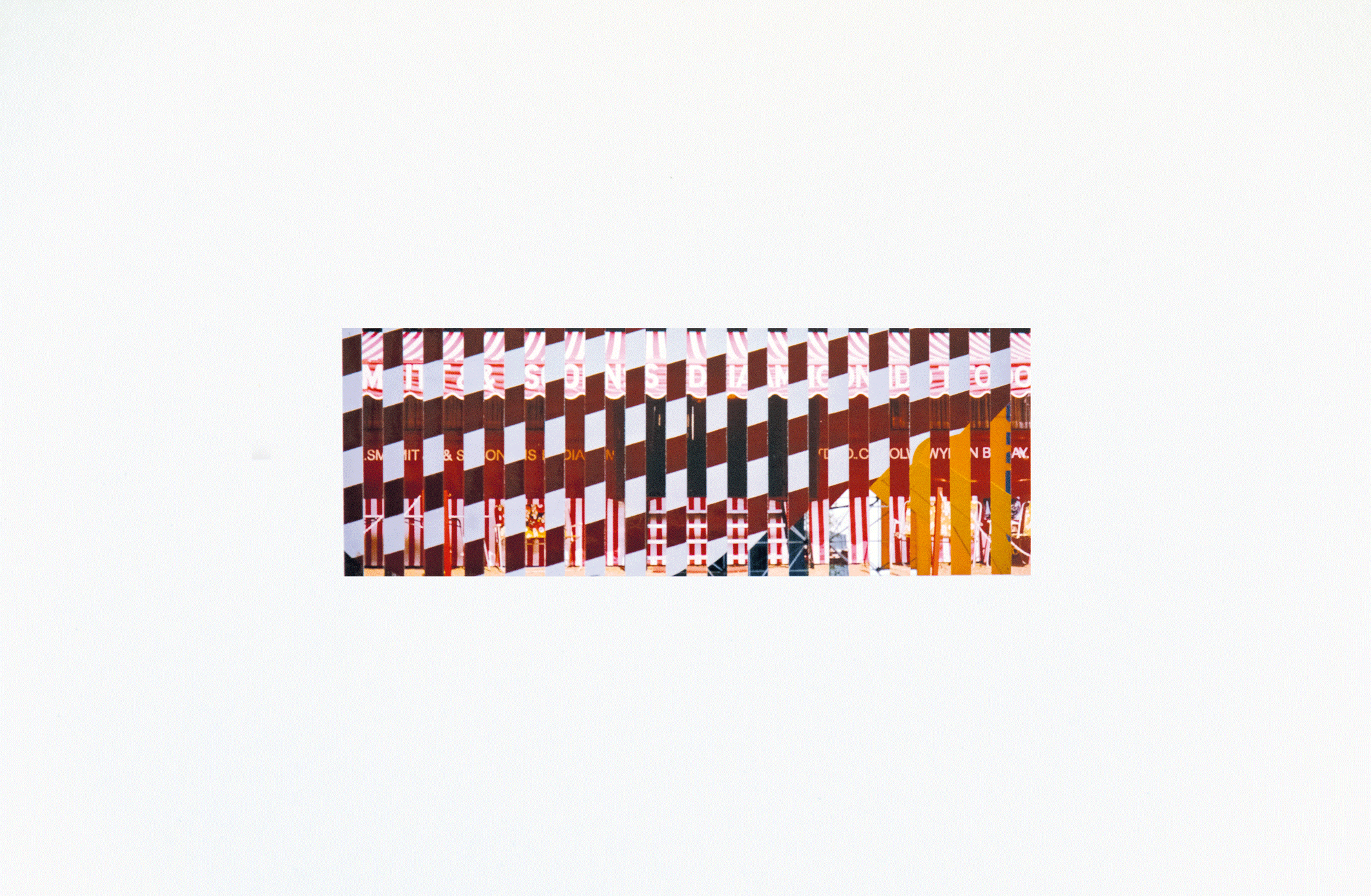

Undoubtedly, Gábor Palotai was always preparing to be an artist. Even before he had begun his studies at the Academy of Applied Arts, his graphic works appeared in the cultural weekly publication Élet és Irodalom (Life and Literature). It would be interesting to compare motifs of the graphic works published between the first and sixteenth pages of the 7 August 1976 issue of Élet és Irodalom with the formal elements of the much later Unreadable Messages,[10] which received the Red Dot Design Award, but this will have to wait.

For the observant reader, it is in all certainty obvious that a cultural-historical-art marketable appropriation of the works made between 1976 and 1980 and published in this book — in other words, a scholarly and public acknowledgement of their merits — can only begin now. After receiving his diploma, Gábor Palotai left for Stockholm, and he only returned to Hungary once his Swedish passport enabled him to do so safely. It is another characteristic of this period that his departure, in other words, his moving from one European city to another European city, was not a simple act, but a prohibited and often punishable crime under the Kádár regime. It is not insignificant that his thesis, written in dialogue format and connected with his diploma work, begins with a Xerox copy and alludes to Franz Kafka’s short story The Departure. “So you know your goal?” he asked. “Yes…Out of here, that is my goal.”

We could ponder the magical-fetishist form of historical consciousness, which, like the Holy Crown in 1978, has unexpectedly returned to Hungary. Floor upbuilding. But art as an alternative to freedom apparently stands the test of time, and that is always heartening.

Budapest, 4 June, 2017.

Miklós Peternák

[1] In 2015 Gábor Palotai was elected as honorary professor of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME).

[2] Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s. New York: Queens Museum of Art, 1999. Hans D. Christ, Iris Dressler (ed.): Subversive Practices. Art under Conditions of Political Repression: 60s–80s / South America / Europe. Ostfildern: Hantje Cantz Verlag, 2010.

[3] Publius Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses. (The Story of Daedalus and Icarus, Book VIII, line 188). Translated by Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden, et al. http://classics.mit.edu/Ovid/metam.8.eighth.html

[4] Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? 1897–98. Oil on canvas, 139.1 x 374.6 cm. Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Cat. Wildenstein 561. http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/where-do-we-come-from-what-are-we-where-are-we-going-32558

[5] http://nemetheva.com

[6] Historical reference: In Hungary the KSH (Central Statistical Bureau) began to use IBM 370/155 computers for data processing in 1974. https://www.ksh.hu/mult_torteneti_kronologia

[7] Purchase data in 1975 were the following: of the nearly 250 thousand television sets sold, barely more than three thousand were colour TVs. In: Magyarország a XX. században. (Hungary in the 20th Century) Szekszárd: Babits Kiadó, 1996-2000. vol. III. A Magyar Televízió története. (The History of the Hungarian Television) Miklós Kaposy (pp. 459–498) http://mek.oszk.hu/02100/02185/html/516.html#519

[8] Koncept koncepció, szemelvények / Concept Conception, Extracts. Katalógus elõszó / Introduction: idézetek /quotations. Budapest: OSAS, 2008.

[9] Interview with Dóra Maurer (2014) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmgYlxglvKg

[10] https://red-dot-21.com/p/design-products/books/typography/unreadable-messages/